Excerpt from

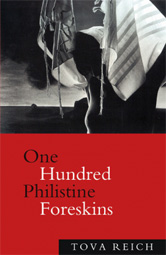

ONE HUNDRED PHILISTINE FORESKINS

She settled Hagar at her breast where the child suckled voluptuously for three full years. Over the eighty-day period of ritual impurity strictly adhered to in Bnei HaElohim prescribed after the birth of a girl — two weeks of menstrual infirmity followed by sixty-six days of blood purification — Temima nursed Hagar in Health House. She nursed Hagar in the cave as she resumed her work on Tanakh with Shira, stopping at each of the stations of womanhood, beginning again with Hava created in the image of man as man was created in the image of God, twice removed. Hagar’s teeth cut through her gums, she grew, she walked, she talked; still she continued to nurse with gusto. Sometimes she would take her mouth off the breast to contribute her commentary. She was particularly engrossed during the weeks of discussion of the suffering of her namesake Hagar the black Egyptian slave. “She so black she blue,” the child declared solemnly, and she opened her mouth wide and wailed, thin streams of pale milk running down her chin. Another time she pulled her mouth off the breast so abruptly she raked Temima’s flesh with her sharp little teeth and exploded into peals of laughter. This happened when Mother Rebekah wrapped her younger son Jacob’s smooth arms and neck in the hairy skin of a freshly killed goat to impersonate his brother Esau and trick his father Isaac into giving him the firstborn’s blessing — for Jacob really was the eldest according to Rashi the commentator-in-chief, Temima noted with a wry smile as an aside not intended for little Hagar’s ears, on the principle of “first in last out,” especially in a narrow passageway with no room for maneuvering. And they actually did succeed in fooling the old man Yitzkhak with this gorilla suit. So vividly ridiculous to little Hagar was this great comic scene from the Tanakh that she could envision it as in an illustrated book for the amusement of children. With milk spraying from her mouth, she burst into hilarity, barely managing to get out the words, Yitzkhak — what a retard!

Your curse be upon me, my daughter, Temima reflected.

Abba Kadosh was present on that occasion. Now and then he stopped by the cave to amuse himself listening to the biblical exegesis of these two concubines with an expression on his face as if he were observing a pair of macaques doing higher mathematics. “Where’s your respect?” he boomed ominously at the child, who was already back to nursing avidly. He glared at Temima. “Sister, it is your duty to rein in your daughter. If you don’t, I will.”

“Out of the mouths of babes,” Temima responded coolly, fixing Abba Kadosh with a withering gaze. And she launched into an exposition of the text to defend her child, asserting that, in fact, Father Isaac — Yitzkhak — may indeed have been “retarded,” afflicted with Down Syndrome, maybe he was what they used to call in Brooklyn a Mongoloid, Temima said recklessly to Abba Kadosh. After all, he was the son of an exceedingly old mother, an off-the-charts old mother, Sarah was ninety years old when she gave birth to him, well past her female cycles by her own admission — and it is common knowledge that the chances of having a Down baby increase exponentially with an older mother, not to mention the age of the father at the time of this birth, one hundred years old — And my husband is so old, Temima said quoting Mother Sarah while staring at Abba Kadosh without backing down an inch. Abba Kadosh in turn glared spitefully at the oversized overaged baby still nursing at Temima’s breast also no longer in the full glow of its youth, but she pointedly ignored the implication and went on, “Or maybe it was just a case of shell shock, after being sacrificed on the mountaintop by his old man. That would do it. Face it, brother, check out the text — Isaac was a guy who just didn’t have a lot to say. And frankly, Abba dear, I don’t know why you of all people don’t consider Father Isaac a little on the slow side. After all, he was our only patriarch who was monogamous.”

Without giving Abba Kadosh a chance to counter, Temima went on to ask if he by any chance knew how old Isaac was when brought by his father Abraham to be bound to an altar on top of Mount Moriah and slaughtered. Thirty-seven years old! Temima answered her own question — according to many commentators. How do they figure that? Since the report of Sarah’s death comes almost immediately after the account of the binding of Isaac, it is believed by some that his mother had simply collapsed and expired, maybe a heart attack, maybe a stroke, when news reached her of what her old man had been up to this time, it was the last straw. Mother Sarah was one hundred and twenty-seven years old when she dropped dead, she had given birth to Isaac at age ninety, which would have made him thirty-seven when he was sacrificed. And the loopy question he asks as he so docilely tags along with Abraham to the land of the Moriah — My father, here’s the fire and the wood, but where’s the sheep for the burnt offering? — and how passively he allows himself to be bound onto the altar without a peep of protest, a thirty-seven-year-old man, there must have been something wrong with him, something not so beseder upstairs. Temima tapped her temple with her forefinger, and shook her head. Three years later, at the age of forty, he is married off to a wife picked out by his father and delivered from the old country by his father’s consigliere, Eliezer of Damascus — Not one of the local Canaanite sluts for my boy Isaac, the old man had said to the Damascene, promise me, place your hand under my testicles and swear. And how old is Rebekah when Isaac marries her? Three! — according to the commentators. How do we learn this? Because her birth is announced immediately after the incident on Mount Moriah, directly before the death of Sarah. So at the age of three, Rebekah waves bye-bye to her father Betuel and her brother Laban and with a shiny new gold ring in her nose she is lifted up onto a camel by Abraham’s right-hand man Eliezer of Damascus and led away, she crosses over from Aram-Naharayim to the land of Canaan — accompanied by her wet nurse. You have to wonder — What kind of normal man marries a three-year-old?

“Out of Tova Reich’s untamed imagination — ferocious, searing, and always on the mark — bursts Temima, a prophetess both majestic and vulnerable, her vision teeming with biblical champions, harlots, and sages, who ascends out of a mundane and hurtful Brooklyn to holy veneration in Jerusalem.

“True to its startling title, One Hundred Philistine Foreskins is a feminist novel like no other — tumultuous with pageantry and pregnancy, wisdom and farce, tenderness and fanaticism, wild faith and earthy folly. If Thomas Mann, with all his anthropological and scriptural vigor, had chosen, instead of Joseph the dreamer, a woman of similar powers and changes of fortune, he might have created Temima. In giving us a visionary Hebrew hero, Mann missed his chance at an oracular Hebrew heroine. But Tova Reich, herself a daring seer, has not.”

— Cynthia Ozick

DETAILS

One Hundred Philistine Foreskins

By Tova Reich

Counterpoint, 2013

Reprinted with permission

Cover art “Skekhina (65-8)” by Leonard Nimoy

Cover design by Rebecca Lown Design

Buy this book

Hardcover: 9781619021075

Paperback: 9781619022805

Back to Book Excerpts