Editing Philosophy & Other Thoughts

“Writing is the art of the second thought.”

—Jack Cappon, quoted in The Elements of Story: Field Notes on Nonfiction Writing by Francis Flaherty

Editing Philosophy

Editing is not about the grammar police patrolling through your creation with heavy boots, commanding what you may or may not do. Editing is ideally a mediation between writer and reader: the editor advocates the needs and expectations of the reader while advising the writer on how to most effectively reach that reader. The best editing strives for the continuity and flow needed to keep the reader’s attention engaged and in the text — the reading equivalent of being so absorbed in a film you forget you’re in a packed theater. It can take much less than an incorrect subject-verb agreement to startle readers out of that spell, or, worse, to prevent their entering it; indeed, a monotonous rhythm can be almost as distracting and discrediting as outright grammatical errors. Some of my personal pet peeves: repeated use of either the uninspired (“the day was ever so muggy”) or overly inspired (say, a minimum of three adjectives for each noun). Even just overuse of “specialty” words (myriad, for example) — which ideally would be only sprinkled through the text, enhancing the flavor of the writing without dominating it — quickly loses its charm.

When asked to do a light edit, I am grammar police, but I wear dainty boots. I tiptoe through the rows of sentences, and will sometimes suggest edits, but I yank only the weeds. I respect that this approach is all that many writers want of their editors. If this is true of you, tell me so up front; I will oblige. But when granted permission to offer more, I act as advisor, consultant, suggesting spots where tighter text would produce a more striking rhythm, where subtle transitions would improve the flow of thought. Sometimes this involves simply moving a phrase or reordering modifiers without deleting or adding anything. However much I may suggest, I strive to retain the feel of the original text, remaining true to its personal style. Good edits should enhance writing, not dominate it.

With some edits I like to explain the thinking behind my suggestions. In many cases it’s not that the text is “wrong” as is — no grammar rules have been broken — it’s that I feel the overall spell has been broken. My role is to identify for you all the spots that might distract a reader; your role is to determine which of those distractions you can live with. ![]()

Concision & Revision

“The first draft is for the author. Every subsequent draft should be for the reader.”

—John Bergez, Bergez & Woodward, Book Development & Editorial Services

Unless you write only for income, then the first draft is the very reason you write. I think of this stage as a form of validation, when one should write in full: savoring, archiving. This is the draft where you don’t want to skimp, so don’t say too little, and don’t equivocate. Honor your experience by expressing your feeling as completely as possible.

But if your second goal is to share your thoughts with others, then you’ll need to create a journey you and the reader take together, one where the reader has bought into the exploration almost as if in collaboration with you. This requires a steady, sober practice of revision — and all the writing experts state definitively that revision and concision go hand in hand. But before we start trimming we need to make sure we’ve conveyed a complete experience to trim. As Susan Bell says in The Artful Edit: “It is very hard to see the right tiny piece to leave until you see the whole thing spread out in front of you.”

SAYING TOO LITTLE

Think of the invitation of your words as a virtual trail of bread crumbs offered for readers Hansel and Gretel to follow. Ideally, when you wrote the draft for you you captured all you had to say without omitting anything. But all too often the tale is incomplete — because the writer knew the full context, and didn’t think to detail it all. But it is a writing peril to assume that the reader can follow the trail, or trial, of your experience with minimal guidance. Otherwise, the reader may encounter the text equivalent of a bread crumb path partially eaten by squirrels. The writer can traverse this path with ease, but Hansel & Gretel are lost in the forest next to a solitary crumb wondering: How did we get here? A moment ago we were on the bus. This is one of the main ways editors assist writers: providing an unbiased, critical read to help identify points at which the reader may get lost.

Another version of saying too little concerns what I call connective tissue. Ideally each sentence flows nicely into the next, and each phrase leads into the next. Sentences lacking narrative flow can feel just as utilitarian as lists, and too much utility quickly bores the reader. Surprisingly, even just a well-chosen word here or there can provide all the connective tissue necessary to create or maintain a smooth reading experience. For example, the second of these sentences to follow doesn’t necessarily flow from its predecessor; it might have appeared anywhere in the parent piece.

“Raised among the scraps and swatches of his father’s tailor shop, Marras is not afraid to push fabrics to their limits in order to serve his artistic vision. His couture debut in 1996 paid homage to the traditions of the past, while at the same time incorporating …”

My edits aimed to lead the first sentence more smoothly to the second.

“Raised among the scraps and swatches of his father’s tailor shop, Antonio Marras, a master of textiles, is not afraid to push fabrics to their limits to serve his artistic vision. How fitting, then, that his couture debut in 1996 paid homage to the traditions of the past while at the same time incorporating …”

(The above text taken from the MARRAS Editing Sample on the Portfolio page.)

SAYING TOO MUCH

But the more common writerly pitfall is the plotting of paths with a surfeit of bread crumbs. (As Sol Stein would put it: “one plus one equals a half.”) While you want readers to believe following your trail will not lead them astray, they don’t need you to recount every step you took en route. This “saying too much” can occur in every writing unit: phrases, sentences, paragraphs — even scenes and chapters.

In editing the diverse submissions that ultimately appeared in I Thought My Father Was God: And Other True Tales from NPR’s National Story Project, Paul Auster found one striking similarity: very often the final paragraph was superfluous, and it was often the only text he cut. The story had been told beautifully up until that point, but the final paragraph might as well have been a joke-teller explaining the joke. In cutting that paragraph, Auster left something for readers to discover for themselves. So trust your readers’ intelligence; let them feel they reach your important realizations with you. To realize, on one’s own, the beautiful truth the author carefully sculpted but never quite stated, is to fully engage with a text. In such moments, readers become your co-conspirators in story.

CONCISION

“Rule 17: Omit needless words.” —William Strunk

“All ideas should be expressed concisely, but without discourteous abruptness.” —Robert Graves & Alan Hodge

“Ensure each word is doing useful work.” —John Bergez

The trouble is: writers love words, and writers can especially love their own words. But, as Sol Stein points out in his chapter “Welcome to the Twentieth Century” (Stein on Writing), the reader of today and the reader of centuries past are two different species. With the amount of distraction we live with now — phone, text, email, IM, Facebook, Twitter, blogs — readers’ interest can easily flag. As such, today’s writer cannot assume the loyalty that, say, Anthony Trollope’s readers offered. To get a sense of just how quickly today’s readers can tire, Sol Stein conducted an admittedly unscientific experiment. He found that mid-Manhattan bookstore browsers spent an average of three minutes considering a work of fiction, after which it was either tucked under the arm or replaced on the shelf.

“Ask the Agent” Andy Ross concurs: “When I started working with fiction, I found that I usually could decide by the end of the first paragraph if a writer had talent. I was a little ashamed of this, so I asked around with other agents and editors. They agreed. This is not to say that I can tell by the end of the first paragraph whether a book is publishable. If the first paragraph makes me fall in love, I’ll keep reading until that first blush of romance disappears. It usually does at some point.… This may seem harsh and unforgiving, but here’s my advice. Make that first paragraph sparkling and brilliant. And after that, make the second paragraph sparkling and brilliant.”

So, you need to hook your reader within the first few pages of your text, ideally in the first paragraph. That might seem like a tall order, but it’s an essential one. “Nothing” words and excessive details bore the reader. After encountering a number of needless words, the reader starts skimming rather than reading — an action one step closer to quitting the work altogether. Conversely, active, surprising diction rouses the reader, conveying there’s much to be missed in not reading further.

“Simplify, simplify.” —William Zinsser

“The ability to simplify means to eliminate the unecessary so that the necessary may speak.” —Hans Hofmann

But oh, revising and pruning can be so painful. Therein lies the beauty of your first draft, the archive in which you’ve honored your complete experience. That draft can remain intact as you work and shape the draft for your readers. And know that writers sometimes need to grieve the sentences they cut, so allow that grief. Create a repository of severed limbs, or create new containers for them. For disparate snatches of text, even the most prosaic writer could venture into Western haiku, which doesn’t require the Japanese 5-7-5 syllable structure. Crafting haiku calls for capturing the essence within a minimum of space — a practice that strengthens the internal red pen needed in revision. It also encourages the writing advice of master teachers: use shorter (Germanic) words rather than longer (Latinate) ones; use few modifiers; choose strong, vibrant nouns and dynamic verbs.

I once cut the following from an author’s text [Olson] as a sample haiku for her:

blissfully obliterated

by the shattering grandeur of being

Cut words are not necessarily bad words; they can be beautiful, as these above are. They’re simply not useful in certain contexts. So, find them new contexts [such as the Haiku Collective], and continue to hone the work at hand.

POSTSCRIPT: REVISION SAMPLES

“Writing is truly rewriting.” —Sol Stein

“Rewriting is the essence of writing well; it’s where the game is won or lost.” —William Zinsser

Large-scale revision efforts of three writing experts:

In the story “Sausage and Beer,” author Stephen Minot cut a two-page flashback just before its initial publication in The Atlantic. He later included the story in his Three Genres: Literary Prose, Poems, and Plays; in that book’s second edition he cut another page, and in the fourth edition he made some additional reductions. (It’s now in its ninth edition.)

In answering the question of if he practices what he preaches re: disciplined revision, Sol Stein noted that he submitted his novel The Best Revenge to his publisher in its eleventh draft. They planned to publish with no additional editing, but he managed to revise it twice more before printing.

This link shows two pages of the final manuscript from the First Edition of William Zinsser’s On Writing Well (10-11).

In the same book William Zinsser provides a sample edit of an author’s first draft; his comments are embedded in brackets within the quoted text (85).

Fictional examples of writing in excess:

“When Gregor announced they were in perfect agreement, Ebenezer’s mouth twitched. I guessed he dare not speak his heart.”

“She tried, but she forgot her friends as soon as they were out of sight. She just didn’t care.”

“Why can’t you love me, baby? Why can’t you?”

“It was a veritable smorgasbord, a bountiful mélange, a splendiferous cornucopia of sights and smells. And tastes!” ![]()

Style & Substance

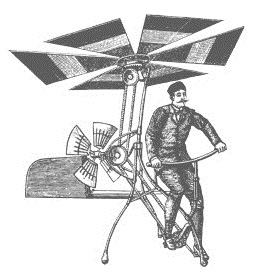

When assessing the efficacy of a piece of fiction or creative nonfiction I think of it in terms of an early flying machine, where the reader is a figure hoping to be taken on a journey. This machine needs to be both solid enough to carry its passenger and buoyant enough to sustain flight. In reading through a piece, and in thinking of it after, I consider two things: In what ways is it solid? In what ways does it soar?

If a work is solid or substantial it effectively and succinctly conveys information. This is perfectly appropriate for some (more utilitarian) purposes. But with no wings, feathers, glue, ropes, tension, release, etc., a creative piece will never get off the ground. It solidly plods; it doesn’t carry us. The reader will continue reading only as a means to an end, if at all.

If a work soars it provides descriptive color, flavor, texture: it enchants, it takes us on a journey. It might carry us far and wide, to places unimaginable, to sights never before seen — higher and higher and … and … A flying machine that lacks a well-thought-out design and integral solid structure, that has perhaps tenuous ropes and glued-on feathers, will come apart at high speeds and melt in the sun. This structure cannot be sustained, and so neither can the journey. ![]()

“Those are lovely notes and beautiful trills, to be sure, but is he actually saying anything?”