Excerpts from

THE BICYCLE DIARIES: My 21,000-Mile Ride for the Climate

I stopped pedaling and looked anxiously at the frontier. In front of me was the California-Mexico border, marked by a white tollbooth-like structure and a large sign that read Mexico in metal letters beneath the country’s coat of arms: a large eagle perched on a cactus with a snake in its talons. It was an hour after sunrise on a Sunday in early December, and the light angled through the cool desert air, illuminating the quiet, dusty town of Tecate just beyond the tollbooth.

If I was trying to be inconspicuous, I was failing. Clad in arm and leg warmers, I essentially wore full-body spandex, and I stood over six feet tall. My bike helmet had a large brim on the front and a cloth attached at the rear, both futile attempts to guard my pale skin from the sun. Between my outfit and my black touring bike with four red panniers, I wasn’t going to blend in south of the border.

But, although I was conspicuous on the road, once I left it I was invisible. Unlike traveling by car, with a bike you can disappear off the highway at any point and set up camp, even just a hundred feet off the road, without a soul knowing where you’ve gone. Thieves can’t rob you if they don’t know you’re there. It’s the greatest sense of freedom; the world was my campground, my living room, my highway. The night before, five miles north of Tecate, I’d easily found a place to sleep, as numerous foot trails led away from the highway, and a patch of desert ground had already been cleared—likely by people also wishing to keep hidden. I wondered how many illegal immigrants, how many of the people I saw working in California during my eight years in the state, had slept on similar patches of ground, staring at the stars.

At twenty-six years old, I was on the adventure I had dreamed of since I was twenty: starting from my home in California, I planned to ride south until I reached the southern tip of South America. I know this sounds a bit crazy. What sane person would camp along the Mexican border—the site of countless crimes and murders—let alone plan to ride alone across all of Latin America? Numerous countries I would travel through are besieged by the residual violence from recent civil wars; Colombia in particular endures an ongoing civil conflict, with nearly a third of the nation under rebel control. Moreover—except for in Chile, where I had studied for three months during college—I had no friends and almost no contacts south of the border. My Spanish was poor, and I had never traveled internationally by bike. Yet for some reason I chose to ignore all of these facts, and instead eagerly planned my route heedless of the risks. I decided I would ride solo across Central America, the Amazon, the Andes, and the wastelands of Patagonia, and I would reach the Earth’s end in just under a year and a half. And not only did I want to bike this distance alone, I wanted to take the opportunity to raise awareness of climate change in the process—a topic I had spent the past four years studying. You might call me naïve. You might be right.

I had discovered bike touring six years earlier. After spending the summer after my sophomore year in college in the “biketopia” of Portland, Oregon, my friend Tom suggested that we “bike to school” in the largest sense of the phrase: riding the nine hundred miles from Portland to Stanford—and doing it in under two weeks. Pedaling a 1980s racing bike I had purchased that summer for $125, and carrying only a sleeping bag, tarp, and change of clothes, I biked with my friend along the rocky Oregon and California coastline. After just a few days, I was hooked.

When you’re biking, no windshield protects you from the rain, heat, or wind, and there’s no wall between you and the people along the road. In a car the scenery appears as if on television, framed by the windows. On a bike, you can practically touch everything you see. The world is right there, in 3-D. You also travel slowly enough that the person at the corner store can make eye contact and offer a greeting as you pass. And, off the highway, the bike becomes a prop for conversation, an excuse to talk. People lower their defenses and open their doors to cyclists in a way they don’t for those traveling by car.

The trip to California took us nine days, riding as much as twelve hours a day. On that journey, we briefly met another cycle tourist who said he’d once taken off two years and biked to Patagonia. Our conversation was brief—I didn’t even get his name—but the idea stuck with me. When we arrived at the palm tree–lined boulevards of Palo Alto, I didn’t want to start my classes; I just wanted to keep heading south. I later read online about a couple different adventurers who had cycled from North America to Argentina, and nearly every one said it was the best thing they’d done in their entire lives. It seemed like the greatest way to see the world, the most invigorating and intimate way to experience the planet. And a trip like this would also be relatively cheap—the main costs just bike gear, food, and a return flight home. I calculated I could save enough cash for it in just two years—that is, once I finished school and started working. From that point on I hoarded my earnings, planned, and dreamed.

I wanted more, though, than just an adventure. I somehow wanted to make a difference in the world—even though, in retrospect, I had a very limited idea of what this world is like. I had spent my entire life in school or labs, and it would be a major leap to head from the classroom to the open road. This bike-tour dream needed some fine-tuning.

So in the meantime I continued with my junior year at Stanford University, studying physics, a major I had chosen just because I enjoyed it, not because I thought it would make me particularly employable. Two years later I earned my master’s degree, in interdisciplinary environmental science. I happened to be interested in the most abstract of global problems—climate change. I found it fascinating how carbon dioxide cycles through the earth’s biosphere, lithosphere, atmosphere, and oceans—and how this odorless, invisible gas has the power to so greatly alter the world’s climate.

I was researching this issue in the years before the award-winning documentary An Inconvenient Truth was released in 2006, before climate change emerged as part of the national discussion. Through reading scientific papers and attending lab group meetings, and working on an ecological experiment studying the effects of warmer temperatures, I had become convinced that climate change poses a real and significant threat to our civilization, and that too few people understood the magnitude of the challenge.

At some point I realized that these concerns dovetailed beautifully with my dream ride, so I decided to “ride to raise awareness of climate change.” I would research the ways global warming was affecting the places I would be biking through—from California to Tierra del Fuego—and I’d encapsulate all I learned in a blog: www.rideforclimate.com. And as I traveled from region to region I’d share what I’d learned with each community, giving talks at schools and speaking with journalists about the very real threats climate change specifically posed to their environment.

In my head, it was a great idea; in practice, I had no idea how I would enact this plan in Latin America. I didn’t even know how to say “carbon dioxide” in Spanish when I started. And, given that the U.S. pollutes far more than Central and South America, raising awareness in those less-polluting lands was a lower priority, earth-wise. And never mind that the original goal of my journey was adventure and not activism, or that multi-year bicycle vacations won’t solve a problem as enormous as climate change. I was just as ignorant about my activist goals as I was about how I would travel in Latin America.

In retrospect, my goal of raising awareness in others was obviously backward—it was my own understanding that changed the most. I saw that climate change is just one of many challenges facing humanity. In many ways, it’s less urgent than ongoing conflicts in the Middle east, or than the daily poverty experienced by billions of people across the globe. And it isn’t something that we should solve by restricting development: most people in the world rightfully want more, not less.

But all that being true doesn’t alter the fact that climate change is real, and my trip gave me a vivid and personal sense of what is at risk—unique ecosystems, coastline settlements, and the livelihoods of countless people. While some of humanity will probably survive its consequences, I know we will regret what we will lose by not taking action.

At the border with Mexico, though, just a month into my ride, none of these thoughts crossed my mind. I didn’t know what lay ahead or how it would affect me. I was just excited that the adventure had arrived, and that I was about to cross into Latin America. I didn’t know my exact route, or whom I would meet, or how I’d raise awareness; I only knew that I’d ride south for months on end, until I ran out of road. I took a deep breath, inhaling the crisp December desert air, and pedaled toward the frontier.

During my last day in Bogotá, Andres, a young geography professor at Universidad de Los Andes, gave me a ride in his small Renault into the mountains forty-five minutes northeast of Bogotá. Having learned about my journey through a friend in the States, Andres offered me a tour of the nearby Chingaza National Park. We followed a road up through fields of potatoes, continuing to climb after pavement turned to dirt. Along the way Andres described studying for his PhD at the University of Florida. In perfect English he said, “Americans never knew where Colombia is on a map, and even if they did, they’d always ask if I drove home. Haven’t they heard of the Darién Gap?” I sheepishly admitted that I had never heard of the Darién until I planned my trip.

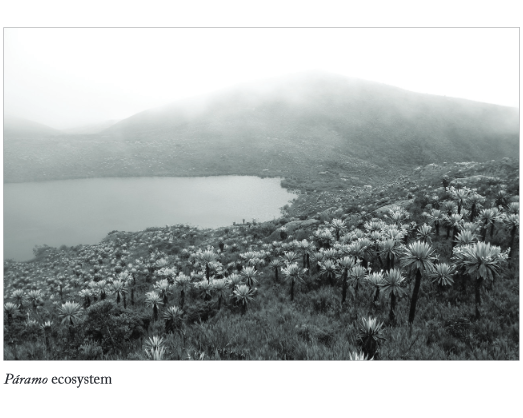

When we passed through the gate to Chingaza National Park, cultivated land gave way to short, spongy grass. We stepped out of the car into the cool, thick clouds. Having planned again, I was wearing all my warm clothes and rain gear. “Welcome to the páramo ecosystem,” Andres said. We were at about 13,000 feet; though we were in the tropics, the temperature hovered in the mid-forties.

Moisture condensed on my rain jacket as a stiff wind blew against us. Following a trail up the hillside we passed grasses, a variety of small shrubs, and mosses clinging to rocks. A small stream of water flowed down the trail, which I ascended in socks and sandals—still my only shoes—with plastic bags over my socks to keep warm. With each step, my feet sunk into the ground as if walking on a wet mattress. As we climbed, the landscape became dominated by what looked like tiny palm trees, ranging in height from one foot to ten and covered in dew. A few had blooms resembling sunflowers. “Those are frailejones,” Andres explained, raising his voice over the wind. “As it’s always cold here, they grow slowly. Some of the big ones are over a hundred years old.”

“You said before that this region is highly susceptible to climate change,” I half yelled back to him.

“Yes,” Andres answered. “Human-caused climate change will create a climate far outside the realm of natural variation. This area was glaciated during the past ice age.” The signs of the last ice age were everywhere around us—lakes in ice-carved bowls in stone, and large boulders called erratics, left behind by glaciers. Andres explained how, during the Earth’s various ice ages, the páramo ecosystem could be found at a lower elevation—one could have found these plants in Bogotá’s valley. But now the ecosystem has retreated to the mountaintops. If climate change warms this area, the ecosystem will have nowhere higher to climb. Andres told me a recent study estimated that if the Earth warms by 2.5 to 3 degrees Celsius (4.5 to 5.5 degrees Fahrenheit), we’d lose 97 percent of the páramo.

“You said this place was important for Bogotá’s water supply, right?”

“Yes, and the water is very clean. You can drink it. Watch.” Andres scooped up water from a small stream and drank it. I filled my water bottle and took a sip; it was cold, clear, and pure. Andres then explained how the spongy ground acts as a huge reservoir, which slowly releases water in a constant stream. Since the ecosystems at lower elevations have less organic matter in their soils, they can’t store as much water. The bulk of Bogotá’s potable water comes from the national park lands.

Andres said, “You know that Colombia has perhaps the greatest biodiversity of any country in the world? We have the páramo, we have the Amazon rainforest in the southeast, and we even have a desert in the far northeast. The páramo alone is home to some two thousand species of plants and animals, many of which are found only in Colombia. All that—all of this—is at risk.”

“Aren’t the mountains taller in Peru and Bolivia?” I asked. “Why couldn’t these species survive there?”

“It is drier down there—a different ecosystem. These plants are found only in Colombia, Venezuela, and northern Ecuador.”

The clouds occasionally lifted, revealing lakes and the rolling hills covered by grass and the frailejones. Tufts of cloud moved with the wind and combed the land. As I had already done several times along my journey, I again found myself in a beautiful, diverse ecosystem that might not still be there should I return.

DETAILS

The Bicycle Diaries: My 21,000-Mile Ride for the Climate

By David Kroodsma

RFC Press, San Francisco, CA

March 2014 | Trade Paper | 413 pages

89 b & w photographs | 12 maps | 2 appendices

www.rideforclimate.com/book

Cover & interior design by Erin Seaward-Hiatt

Back to Book Excerpts